By Vikas Datta

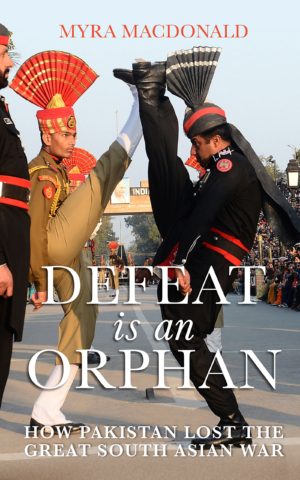

Title: Defeat is an Orphan: How Pakistan Lost the Great South Asian War; Author: Myra Macdonald; Publisher: Penguin Random House India; Pages: 328; Price: Rs 599

What is termed a self-goal in football and hit wicket in cricket has an equivalent counterpart in international politics, and especially international conflict. In this, it is when one side contributes to its own defeat by its intransigence on improvident ideologies and dangerous, discredited strategies. This may have been seen in the South Asian subcontinent’s most persistent and intractable conflict.

Or more specifically, it can be used to describe the outcome of the Indian-Pakistan confrontation over the last two turbulent decades, a mostly indirect and undeclared war which ended rather badly for the latter, argues veteran journalist Myra Macdonald in this book.

And while she makes quite a persuasive case for her premise in the “war”, which she dates from the 1998 tests when both countries declared themselves nuclear-armed powers, to the present year, she doesn’t seem very confident about whether if the lessons been learnt — by either country.

And while she makes quite a persuasive case for her premise in the “war”, which she dates from the 1998 tests when both countries declared themselves nuclear-armed powers, to the present year, she doesn’t seem very confident about whether if the lessons been learnt — by either country.

“It is not so much that India won the Great South Asian War but that Pakistan lost it,” says Macdonald, noting that while the causes were “deeply rooted in its history”, it was Pakistan’s “policy choices” that were responsible too.

Also implicit is that the victor need not puff up and rest on its laurels but strive to safeguard the factors, beyond military strength or nationalistic fervour, that enabled its primacy.

The author, who arrived in India as Reuters’ bureau chief in 2000, says in her stint, both countries came close to war on one occasion at least, and “tantalisingly near to a peace agreement on Kashmir on another”, but “by the second decade of the 21st century, peace remained as elusive as ever, and the chances of a settlement on Kashmir had become vanishingly small”. The “most striking change”, however, was in the countries’ profiles, as she brings out in a balanced perspective.

Macdonald notes that after leaving the news agency, she decided to revisit this recent history, which she had experienced as a journalist, to “review what had happened without the pressure of daily news, pulling at the threads that are often overlooked in the urgency of the moment”.

The book, divided into a series of episodes and eras, is hence a “product of multiple viewpoints” from all around the region as well as the world, both when she was reporting as well as more recently where she interviewed serving and retired officials from both sides.

While Macdonald does seek to start her “great war” timeline from the nuclear tests conducte by both countries in 1998 — contending that while the rivalry does date back from 1947, it had “accelerated” from then on — she actually begins her account with a happening at the dawn of the new millennium — the hijacking of IC-814 and its implications.

Subsequently, she deals with the nuclear tests, the Lahore summit and the Kargil war, the relations between Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Gen Pervez Musharraf, including the Agra summit, other events in the year, especially in the run-up to 9/11, the December 2001 attack on the Indian Parliament and the trial of Afzal Guru (in whose troubled story, both countries don’t come out very good).

This is followed by the Indian mobilisation on the borders, a short history of Kashmir over 150 years, the peace process between 2004 and 2007, the Mumbai attacks, and the subsequent course of India-Pakistan relations, down to the unrest in Kashmir after Burhan Wani’s killing and India’s “surgical strikes”.

Also in what is one of the most important and insightful parts of the book, there is a chapter on Pakistan’s tortuous relations with its northwestern areas and misreading of its people, in a deleterious after-effect of colonial attitudes.

And while readers from both sides may think they know all these events well, Macdonald frequently brings up some unknown bit or insight. There is, in fact, a wide range of keen insights — though likely to be unpalatable to one side or the other — making this a rewarding and invaluable read.

Two most prominent ones for Indians will be on the role of media post-Kargil and an echo of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto’s politics here and now. (IANS)